Among the things that I, and all priests, are ordained to do is to administer the sacraments of the Church. And no one in the Church should be in any doubt about this because during the ordination service, the bishop asks all the candidates for ordination this question:

Will you faithfully minister the doctrine and sacraments of Christ as the Church of England has received them, so that the people committed to your charge may be defended against error and flourish in the faith?

To which all those wishing to be ordained as a priest must answer,

By the help of God, I will.

Along with the vast majority of the worldwide Church, the Church of England recognises seven sacraments: Baptism; Confirmation; Holy Communion; Reconciliation; Anointing the Sick; Holy Matrimony; and Ordination. Only a bishop can confirm and ordain people so, in practice, a priest can administer five of the sacraments. Of course, in order for a priest to administer the sacraments, people have to want to receive them and, leaving aside the dearth of people who want to be married in church these days, of the five sacraments that I as a priest can administer, two are sadly, I might even say woefully, underused; anointing of the sick and reconciliation, or to give that sacrament it’s more common name, confession.

On Tuesday of Holy Week I, along with many other priests and people attended the Chrism Mass at Manchester Cathedral. That’s a service at which the clergy renew their ordination vows and the Holy Oils, including that used for anointing the sick are blessed by a bishop. At the end of the service, the bishop of Burnley, who celebrated the Mass and blessed the oils urged the clergy to ‘use the oils generously’, to ‘have healing liturgies so that people can receive this sacrament and be drawn into closer relationship with Christ.’ At which point I thought, ‘I do have healing liturgies, but no one comes to them!’ Actually, that’s not entirely accurate because some people do come to them, but very few people do, and it’s always the same few who come to them.

I must admit, I find it very strange that people are so reluctant to take advantage of the sacrament of anointing. All of us, at times suffer in body, mind or spirit and so we all need healing. So why then, are people so reluctant to come to God, to be anointed with oil in the name of the Holy Trinity, and to seek his help when they’re in need of help and healing? And if the answer to that is because people think it’s something only Catholics do, and by that mean Roman Catholics, I’m sorry, but those people are utterly and completely wrong. The sacrament of anointing is recognised by the Church of England, a Church which, by the way, has always, and only ever claimed to be a Catholic reformed Church. But in any case, anointing the sick with oil is one of the very oldest practices of the Church, and predates the Roman Catholic Church by about 1,500 years. We know that with certainty because we read this in the Letter of James:

Is anyone among you sick? Let him call for the elders of the church, and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord. And the prayer of faith will save the one who is sick, and the Lord will raise him up. And if he has committed sins, he will be forgiven. Therefore, confess your sins to one another and pray for one another, that you may be healed.

We’re sure that was written by James, the brother of Jesus, and leader of the Jerusalem Church, and it was probably written no more than 15 years, and perhaps less than 10 years, after the Lord’s Resurrection.

In that passage from his letter, James also speaks about the need to confess our sins, and that brings us to the second woefully underused sacrament I spoke about, the sacrament of reconciliation, or confession.

This past week, I heard a confession for the first time in a long time. In fact, if memory serves me correctly, the confession I heard this past week was only the third confession I’ve heard since I’ve been the vicar in this benefice. I said this was a sacrament that’s woefully underused and when you realise that I’ve only been asked to hear confessions three times in 5 years, I think you’ll understand why I said that.

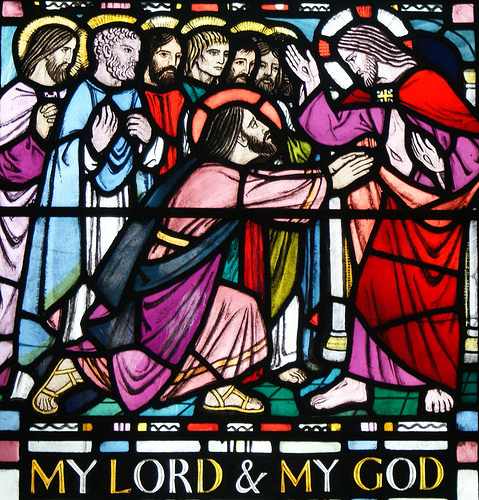

I do know that this is a sacrament people are reluctant to use for a number of reasons. One very common reason for not using the sacrament of reconciliation is that it is something only ‘Catholics’ do. I think the fact that the Church of England recognises the sacrament of reconciliation, and what we read in the Letter of James should answer that objection to using the sacrament. But more than that, the confession of sins and the pronouncement of absolution by the Church has clear dominical authority. In this morning’s Gospel do we not hear Jesus himself say to his disciples,

“Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven them; if you withhold forgiveness from any, it is withheld.”

So Christ clearly gave his Church authority to pronounce the forgiveness of sins. But how can the Church pronounce forgiveness of sins if it isn’t aware of them? I think it’s obvious that in order to forgive we have to know what needs to be forgiven. So to take advantage of this wonderful gift that Christ gave to his Church, the authority to say to people that their sins are forgiven, the Church needs to know what those sins are. And so people need to confess those sins.

Obviously, no one likes to admit they’ve done wrong, and we often don’t want others to know what we’ve done wrong, so pride and embarrassment also stop people from making confession of their sins. But pride itself is a sin, and one of the worst sins. So if pride is stopping anyone from using the sacrament of reconciliation then, to coin a phrase, they’re just heaping more coals on their heads by being too proud to confess their sins.

Embarrassment though, whilst it might be a symptom of sinfulness, isn’t a sin in itself. In fact and in a sense, being embarrassed, ashamed about what we’ve done, and feeling uncomfortable talking about it is a kind of self-inflicted penance for our sins because we wouldn’t be embarrassed about what we’d done if we hadn’t done it. But there’s no need to be embarrassed coming to a priest to make your confession. In my 17 years as a priest, I’ve never heard anyone confess to anything that I’ve been either shocked or disgusted by. A priest is also bound by what’s often called the Seal of Confession, they’re forbidden by canon law from repeating anything that’s said to them in confession, to anyone. And a priest won’t think any less or worse of you because of the sins you confess because we’re all sinners too. In fact the very last thing a priest says to the penitent, the one who’s made their confession, after absolution has been pronounced is this:

My dear brother/sister in Christ, God has put away your sins, go in peace and pray for me, for I too, am a sinner.

So there’s no pride or holier-than-thou attitude in the priest in confession. Priests don’t absolve people from sin, we can’t because we’re sinners too. What a priest does in the sacrament of reconciliation is pronounce God’s forgiveness by the authority that Christ gave his Church to do that.

Another objection to using the sacrament of reconciliation is that, as it’s God who forgives sin, there’s no need to go to a priest to confess your sins. Many people do take that approach, and for them, the General Confession at the Mass or Eucharist is enough. But the problem with this is one of certainty. If we don’t receive the spoken assurance of absolution from the concrete sins we’ve confessed to, how can we be certain that we’ve been forgiven for them? It’s a problem summed up by the German Lutheran, Dietrich Bonhoeffer in his book Life Together. Bonhoeffer said this;

Why is it that it is often easier for us to confess to God than to a brother? God is holy and sinless; he is the just judge of evil and enemy of all disobedience. But a brother is as sinful as we are. He knows from his own experience the dark night of secret sin. Why should we not find it easier to go to a brother than to the holy God? But if we do, we must ask ourselves whether we have not often been deceiving ourselves with our confession of sin to God, whether we have not rather been confessing our sins to ourselves and also granting ourselves absolution. … Who can give us the certainty that, in the confession and forgiveness of our sins, we are not dealing with ourselves but with the living God? God gives us this certainty through our brother … A man who confesses his sins in the presence of a brother knows that he is no longer alone with himself; he experiences the presence of God in the reality of the other person.

Anointing of the Sick and Reconciliation. Christ gave these great gifts and great authority to his Church for a reason. He gave us these things to bring us healing in body, mind and spirit, and to give us the assurance of the forgiveness of our sins, so that our relationships with God, with our neighbour and with our own selves can be put right. By the authority Christ gave to his Church, I’m here as a priest to make these things available to you and for you. So I urge you to make use of them.

Amen.

The Propers for the 2nd Sunday of Easter can be viewed here.